Michlyn Caffrey, Head of Subject for English Mastery, a subject excellence programme from Ark Curriculum Plus.

We often hear that in today's world, communication is power. But how well are communication skills and oracy really being taught in our classrooms? The recent report from the Commission on the Future of Oracy Education in England, and Ofsted’s English Subject Review raises some big questions about the way we teach oracy in schools—and why it is something we need to address now.

As Geoff Barton compellingly states in his introduction to the Oracy Commission report:

Now more than ever, we need our young people to be equipped to ask questions, to articulate ideas, to formulate powerful arguments, to deepen their sense of identity and belonging, to listen actively and critically, and to be well-steeped in a fundamental principle of a liberal democracy—that is, being able to disagree agreeably.1

So where do we begin? What steps as curriculum and pedagogy experts can we put in place to ensure that oracy is an essential part of every teacher’s toolkit? How can a subject excellence programme like English Mastery support the recommendations from these key reports?

The Oracy Commission helpfully provides a definition agreeing that oracy can be best defined as:

Articulating ideas, developing understanding and engaging with others through speaking, listening and communication.2

It comprises three interrelated, overlapping and mutually reinforcing components:

By having this shared definition of oracy, curriculum and school leaders can begin to identify where oracy can sit within the education framework.

One of the key recommendations of Oracy Commission report is for oracy to be equally recognised, valued, and resourced alongside reading, writing, and arithmetic as a cornerstone of education. There should be an intentional development in skills for spoken language that should be explicitly taught just like teaching algebra in maths.

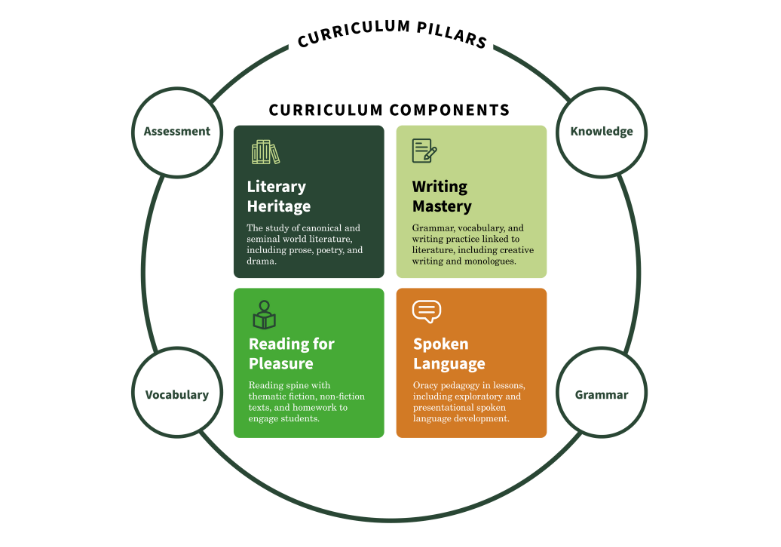

English Mastery welcomes this recommendation as we have always viewed oracy as essential in learning and engaging with the subject of English. We have long included oracy elements in our curriculum and have now explicitly drawn these together to make spoken language the fourth component in our curriculum model.

Ros Wilson captures a common frustration that ‘oracy is not just speaking and listening’. 3 To have impact, oracy must not be an ‘add-on' or tick list. It is not simply another task to slot into an already packed lesson. Instead, we should consider what the best type of instruction would look like for each part of learning, and plan how - and whether - discussion, debate, questioning might better develop and secure students’ understanding and engagement.

Claire Sealy effectively highlights that oracy is not a ‘thing’ that we do in a performative ‘look-at-us-doing-oracy’ dance. It is a range of teaching practices, whole school routines and subject specific curricular objects. 4 English Mastery has always positioned oracy and spoken language as a curricular goal in its own right, and never as a means to an end.

A recent English Subject Review points out few schools design or follow a curriculum to develop spoken language. Schools are not always clear about how to teach the conventions of spoken language that enable students to speak competently in a range of contexts.5

The Oracy Commission report identifies and divides the oracy skills young people need to develop at school into four distinct and

This is a helpful framework for schools to determine their focus when teaching different aspects of spoken language.

English Mastery supports teachers by:

The Oracy Commission report highlights that oracy is also a pedagogical issue, involving choices a teacher can make in the classroom and how they deploy talk to elevate learning within their subject or phase.

In English Mastery we explicitly support teachers to foster and engage productive talk with pupils. We do this through

In addition to the above talk tasks, English Mastery explicitly develops exploratory talk. Exploratory talk involves students critically and constructively interacting with each other’s ideas and making their reasoning visible through talk. The Oracy report highlights that students benefit from support and structures to develop understanding of what exploratory talk is like. It also recognises that cognitively challenging talk is crucial in dialogic talk, demonstrably improving engagement, learning and attainment. 7 Additionally, the report recognises that the importance of cognitively challenging talk in dialogic talk, which evidence suggests makes a demonstrable difference to pupil engagement, learning and attainment. 8

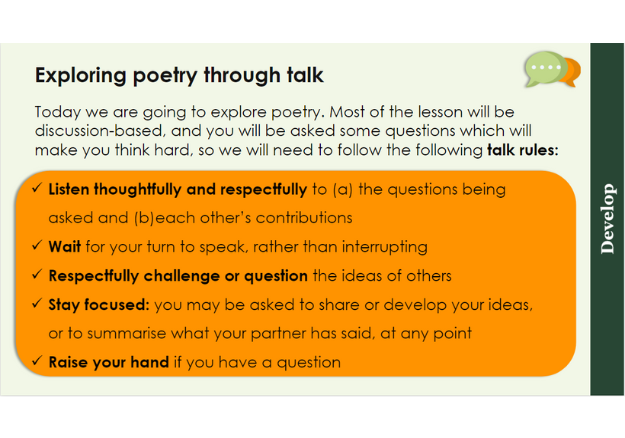

But what might great practice look like in the classroom? Below is an example of an English Mastery discussion-based lesson, where students are encouraged to explore symbolism and approaching an unseen text through exploratory talk and dialogue.

Figure 1: Example of exploratory talk in English Mastery Literary Heritage lessons

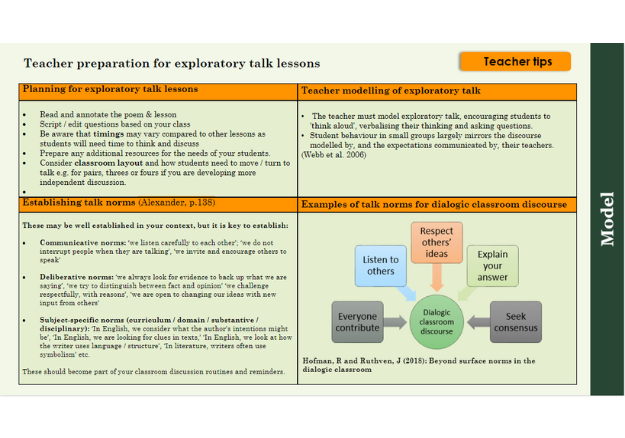

Rules for talk are established at the start of the lesson, to ensure that talk is structured and productive. Pedagogically, we support teachers to consider how to plan for structured talk in the lesson and ways in which this can be modelled as shown in the explicit guidance below.

Figure 2: Example of teacher guidance to support exploratory talk

English Mastery also provide similar resources to develop dialogic talk via debate and drama lessons for each Literature unit.

The report emphasises the need in the national curriculum for young people to learn about spoken language and communication and all its forms because this supports them to make informed choices about what language to use in specific contexts and enables them to understand and value their own and others’ ways of using language.9

A key recommendation from the report is to have a revised English Language GCSE to engage students in the study of spoken language. This will empower students with greater appreciation of their own language identities and the critical awareness and agility required to navigate the complexities of language in today’s world. 10

Being a part of The English Association’s Summit on the Reform of the English GCSEs, English Mastery advocates for:

the study of broad linguistic knowledge, including etymology, morphology, sociolinguistics, language acquisition, and linguistic behaviour (e.g. code switching, exploratory talk, register)11

We know that there is even more work that the programme can do in this area, so we are exploring how a spoken language investigation unit can also be integrated into our KS3 curriculum in the future.

The key findings and recommendations from the Oracy Commission Report underline the longstanding design principles and newer programme developments of English Mastery. Oracy is front and centre of English Mastery, and the holistic nature of our curriculum means that spoken language enhances other aspects of the English discipline. Not only are we fostering confident speakers and listeners, but our spoken language curriculum creates a foundational base to develop better writers and critical readers. It is exciting to continue to support our community of teachers to move oracy more centrally into the experience of all young people in their journey through English education.

Related Posts